I am black and I am British.

There exists a false dichotomy which asserts that I must be one or the other. But the truth is, I love being both. Everything about blackness is beautiful to me. From the warmth, depth and richness of our melanin to the medley of cultures, musical styles, art and unmatched cuisines intertwined with unique humour, tenacity and joy.

It’s not all sugarplums and fairies. We’ve been through pain. We are complex and multifaceted. Extraordinary yet normal. Resilient yet vulnerable. Long story short, I just really love black people. And specifically, my Nigerian heritage.

Black, to me, represents the unconditional love of my immediate and extended family. It’s all of our memories; the lows as well as the highs. In a way, it’s all I’ve known.

But at the same time, I’m ‘quintessentially British’.

I was born and raised in Britain. I love tea, fish and chips, dry humour, and complaining about the weather. I’m awkward, too polite, say “I reckon” and think about hedgehogs every time I cross the road. If you’ve ever been in my car, you’ll know that my radio never deviates from Magic 105.4.

If I had a penny for every time I’ve been told I “act white” or “sound white”, I’d have a lot of pennies. Don’t be fooled, though – this hasn’t only been from white people (complete with utter astonishment).

I’ve been called a ‘coconut’ by people who consider themselves to be ‘really’ black. “White on the inside, brown on the outside.” (Synonyms include Bounty, Oreo etc. etc.) Who knew that a piece of fruit could have such ‘fraternising with the oppressor’ undertones.

Why wasn’t I allowed to claim parts of my identity as my own?

I remember telling some of my non-black friends about the term ‘coconut’ when I was around 14, and trying to explain to them why I didn’t appreciate it. My Asian friends seemed to understand – it was a widely used term in their community, too.

But unfortunately, it was harder to convince some of my Caucasian friends. I was swiftly shut down by one of my pals, who told me that I was being offensive because “…why wouldn’t I want to be white?”

My point was sorely missed.

White isn’t bad. It’s just not what I am.

Why wasn’t I allowed to claim parts of my identity as my own? Because they didn’t fit into a stereotypical idea of blackness?

My accent, enunciation, mannerisms, hobbies, interests and personality are formed not only by my race and heritage, but by the environment I was born into and brought up in. I like British things because I’m British. I speak well because I was taught to. I didn’t understand what either of those things had to do with being white.

Why does ‘British’ have to be synonymous with ‘white’?

Are ‘black’ and ‘British’ mutually exclusive?

Why can’t I just be black and like the things I like?

Must my blackness be challenged at every stage, from every side?

‘But ultimately, I was also a child. I just wanted to fit in.’

I guess I knew the answer to these questions in some respects.

People respond to what they see. A majority population is used to seeing variation within their people. When a smaller, unfamiliar group enters that space, it’s easier to reduce them to singular characteristics than to acknowledge their true heterogeneity.

At best, it’s a simple lack of exposure. At worst, a lack of concern for the ‘minority’.

Even at that relatively young age, I knew that I didn’t want the parts of me that were seen as ‘refined’ or ‘acceptable’ or ‘relatable’ to be conceptualised as ‘white’.

I knew deep down that black people were not a monolith and that we could have varied interests and be good at things – whilst black. I knew that we could be smart, articulate and versatile – whilst black.

But ultimately, I was also a child. I just wanted to fit in.

So, whether ‘black’ and ‘British’ were mutually exclusive or not – I felt I had to choose.

I hid my ‘whiteness’ from my black peers, who at times made me feel like I was trying to be something I was not.

I played into my ‘whiteness’ for my white peers, to avoid being asked why I was ‘acting black’ if I ever strayed.

It was exhausting.

The British Nationality Act

Black folk have been around in Britain for a while, at least as early as Roman British times.

So it’s somewhat bizarre to think that the idea of black people integrating into British society is still such a foreign concept. Is it that people still aren’t used to seeing us around? Or is there still a conscious/unconscious desire to “Keep Britain White”?

All this had me thinking…

I wonder what it was like to be black in Britain at a time when its black presence was rapidly becoming visible.

In 1948, the British Nationality Act gave individuals born or naturalised in British colonies the right to settle in the UK as ‘citizens’. This, as well as active encouragement from the British government to help clean things up after the war effort, led to a “wave of mass immigration.”

The new arrivals initially hailed mainly from the Caribbean, and later from colonies like Nigeria, Ghana, and India amongst others.

Fast forward 20 years, a member of the Conservative party had this to say in response to mass immigration and to a proposed bill that sought to make it “illegal to refuse housing, employment, or public services to a person on the grounds of colour, race, ethnic or national origins in Great Britain.”

“We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependents, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant descended population,” said Enoch Powell on 20th April 1968, “It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.”

In response to the bill itself, he went on to add that “the immigrant and his descendants” should not be “elevated into a privileged or special class” and that citizens should not “be denied [their] right to discriminate in the management of [their] own affairs.”

2 years later, the Conservatives won the 1970 general election in a “surprise victory.” I’m not one to get political, so I’ll leave you to draw from that whatever conclusions you will.

Black In 1960s Britain

A story of a young Nigerian expatriate family.

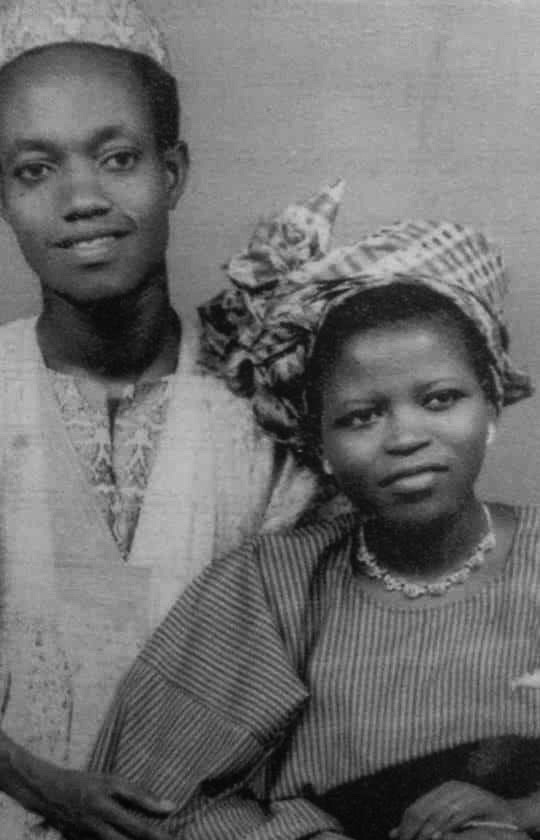

These two handsome-looking people are my maternal grandparents, born and raised in one of Britain’s most recognised colonies; Nigeria. By 1962 – two years after Nigeria gained independence from British rule – they were both living, studying and working in the UK.

Like my grandparents, anyone who arrived in the UK from former colonies (or, as they were now referred, ‘Commonwealth countries’) before 1973 was granted the right to remain indefinitely. (Although, the government kept no record of these individuals, which disproportionately affected the Caribbean diaspora – read about the Windrush scandal).

The experiences of individual black people in Britain in the ’60s and ’70s, or indeed throughout history, are far from universal. But I was curious to pick Grandma’s brains and find out a bit about her personal experiences as a young Nigerian expat. I wanted to hear her perspective on life in Britain in those times for herself (a health visitor turned fashion designer), her late husband (a budding civil engineer) and their young family.

So, without further ado, here’s a breakdown of our little virtual interview.

“How are you, Grandma? We finally made it.”

“Can you hear me?”

“Yes, I can hear you, Grandma. I can.”

“Okay, okay. I can see now that you resemble your grandmother [my dad’s late mum]. I saw that her picture they put there. I think she was younger when they took it.”

“Ha! Yeah, it’s true. Everyone says that!”

“So, what are we doing now?”

“I’m gonna go through some questions with you. I sent them to you on WhatsApp so you should be able to look at them on your phone, but I’ll ask them as we go along as well.”

“Madam. Madam! Listen, oh. Talk. Slowly.”

“Slowly, slowly, yes!”

“Can you understand my own tune? The way I speak?”

“Yes, Ma.”

“Okay.”

Chapter 1: The Nigerian Dream

We start off with a quick introduction to the lady herself, and I ask what brought her to the UK at the age of 24.

“My name is Adedoyin Titilola Shodipe. I got married to Mr Owolabi Ogunlesi and changed my name to my husband’s name, Adedoyin Titilola Ogunlesi. After we got married, my husband proposed to go to study in London. I agreed, so he went in 1961. About a year after, I followed.”

She tells me that their plan was always to bring their skills back to Nigeria, to help develop the nation and build a home for themselves in their motherland.

“Before that, I was working with Lagos Town Council as a health visitor. I resigned from my post and came to England to join my husband.

“On arriving, I thought I would continue my work which was caring for children – I had been working in an infant welfare clinic. But on getting to England, I couldn’t – because it would mean leaving my husband and going to live in a hospital to start studying nursing. And unfortunately, I got pregnant.”

I chuckle.

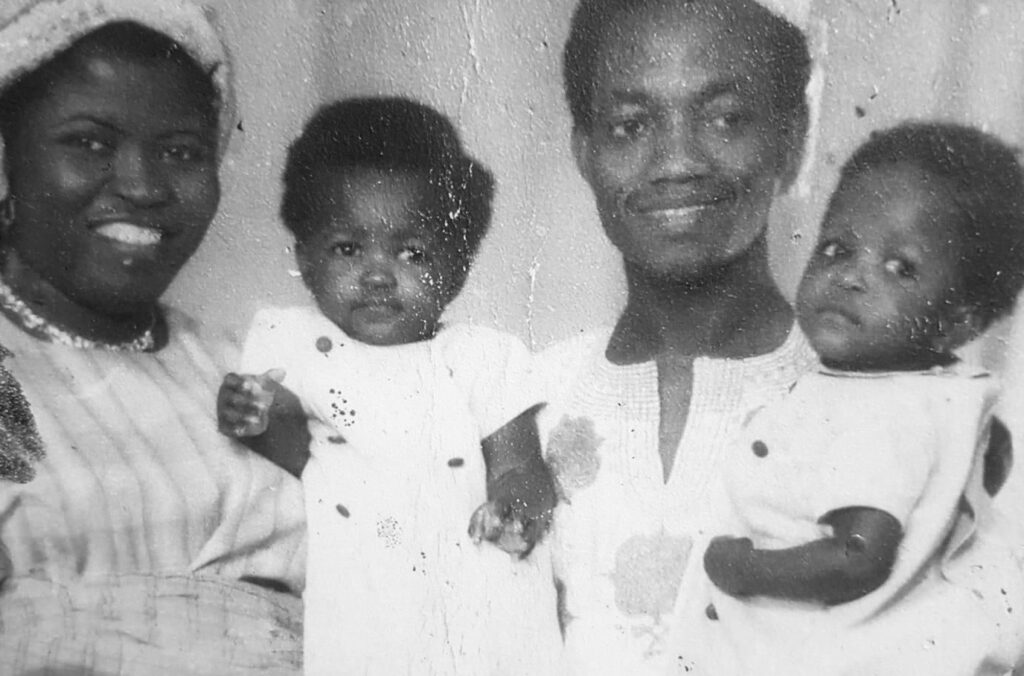

“When I got pregnant, they examined me and said, ‘you are expecting twins.’

“We thought about it several times, then I said I would change my course. I wouldn’t leave my children at home to go and start living in a hospital. I looked for several other courses, and finally I settled on fashion design. I settled on it because it was my mother’s work, and I knew a bit about it before going abroad.

“I entered college and started studying. I left my twins with a nanny whilst studying. It wasn’t all that easy… it wasn’t all that easy, but I wanted to study.

“After my first and second year, my husband was transferred to Manchester to work on a project which would take several years. So I said it’s better if I also move to Manchester. We left the children with a live-in nanny in Kent and we would come to visit, until we decided to bring them to Manchester so that we could be together.”

“By that time, I was advancing in fashion design. I continued my studies at the Manchester [Metropolitan] University and by the grace of God, I did well. I think that will do for the beginning…”

Chapter 2: Black & White

We discuss Grandma’s line of work in a little more depth, then I’m curious to know whether she’d worked any jobs outside of fashion.

“At first, when we were in London – before I joined fashion fully – I was doing some odd jobs to pay rent, to pay bills. Then we got settled on our jobs. We were working at our jobs and at the same time, we were studying.”

“Can you give me some examples of the kinds of “odd jobs” that you did?”

“The one that I remember very well was at a catering centre – cooking, washing plates and all the rest.”

With all this helpful context, I’m eager to get into the crux of the conversation.

“Were you aware of your ‘blackness’ before coming to the UK?

“Before I went to the UK, I knew I was black. I worked with a lot of white people.”

“Oh, okay! In Nigeria?”

“Yes. When I left school, the first place I worked – I think I’ve told you that – was infant welfare. At that infant welfare, I was working as a health visitor. And our doctors – all the ‘oga-ogas’ [the big bosses!] – they were white.”

“Ahh. Because of colonialism?”

“Eh-hen. [Yes.] Because we were just coming out of the grip of… you know we got our independence in 1960. Until 1960, they were ruling us. There were many of them, British – mostly British. Until we got our independence, and they started going home gradually.

“We really enjoyed them. At that time, there was nothing like discrimination.

“And when we arrived in Britain… before I was admitted into college, I had to pass my English GCE. Right from the time I was doing my GCE, I started moving with a lot of white people. When you’d have about twenty white people in a class, you’d have about three or four black. But we were enjoying ourselves. Everything was okay.

“Discrimination, black, white… we were feeling it gradually… ‘you’re black, I’m white – where do you come from?’ But it was still okay.”

“Yeah… yeah.”

I think about all the times I’ve been asked this question.

To an extent, I can understand why they would ask someone as ‘obviously foreign’ as Grandma. Especially as mass immigration was still relatively new. But it’s the ‘you’re black, I’m white’ that gets me. It almost feels as if that’s the unspoken train of thought that occurs every time someone asks me, “Where are you [really] from?”

‘I’m not black, you’re black!’

Grandma goes on.

“I would say even until I finished and came home [to Nigeria], I never felt that they hated me. Because by the time I started making dresses, most of my customers were English. I didn’t have a lot of black people as customers. Most of my friends and my customers, they were white.”

“Interesting. And you also mentioned that in Nigeria, there were a lot of white people because of colonialism, but that you were getting along?”

“Me, oh! I was getting along with them very well. And when I got to Britain, the same thing.

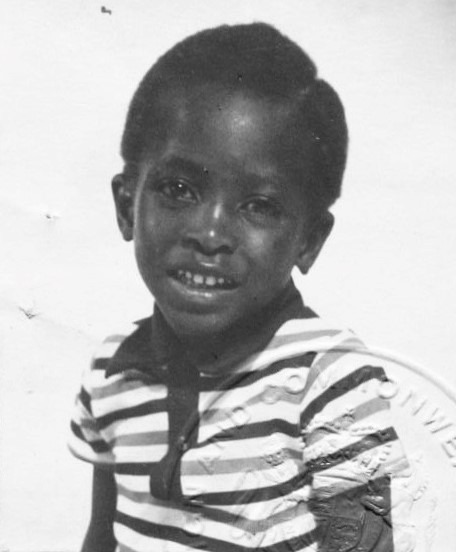

“Even your mother – my twins – they didn’t realise that they were black. Did you know?”

“No, I didn’t!”

“They didn’t know that they were black. So, one day we were talking – it was your mother! She said, ‘Get away from me, you Black!’”

“Who did she say that to?!”

“To me! So, I took her hand and I placed it near my hand. I said, ‘Look at the two.’ The white person that was with me, I called that one and said, ‘Please, bring your hand.’ So, three hands. I said, ‘Who is black? Who is not black?’

“She said, ‘I’m not black, you’re black!’”

After we get done laughing, we continue.

“They didn’t realise that they were black. Because of the relationship…”

“…that they had with white people.”

“Yes. With everybody, with everything. So cordial. As we were living in Manchester, we decided to buy a house. We bought one on Montrose Avenue and we were really, really happy in that area. That was where Yinka was born.”

“So, it sounds like, in general, there was a good relationship – for you, personally – with white people.”

“Ohhh, yes – especially with my job. If they want to make wedding dresses, they come to me. If they want to make this or that… my house was always full. 90% of my customers were white because we didn’t have many black people in Britain.”

“That’s true, that’s true. Did you have any black friends? Like, any black families or African families that you knew?”

“Oh yes, yes. In our area, we had one from South Africa. The husband was a doctor and the wife was a nurse, Dr and Mrs Mbolekwa. They were my very close friends. Anytime I was busy or couldn’t take my children to school, she would take them. By that time, Yinka was already with us.”

Chapter 3: Alligators & Crocodiles

After a very positive start, I wanted to explore the other side of things.

“What was your experience being a young black woman in the UK at that time? Did you experience any racism?”

This question takes us back to her early days in the fashion industry.

Whilst enrolled at college, Grandma started her first job in fashion where she worked as a machinist.

“I met one boy there, he was about 23 or 24. I was working on the machines, he was working on patterns. He was our grader.”

[For those of you who, like me, know nothing about fashion design; grading is the process of scaling a sample pattern up and down into different sizes.]This colleague of Grandma’s phoned her one day, asking about her studies. She relates their encounter and the professional relationship that ensued.

“‘You go to The Toast Rack!’ he said.”

“The what rack?” I interject, bewildered.

“That was what they called it in that area,” she explains. “Because it was built in the shape of a toast rack. But its name was Hollings College [Manchester Metropolitan University, Hollings Campus].”

They began to discuss topics surrounding his work in pattern and grading.

“He asked me, ‘Can you grade well?’

“I said no, so he said he would teach me. We started working together; he would teach me at break times. We became very close.

“One day, I saw an advertisement in the paper for a grader at Alligator Rainwear. I phoned them and spoke to one Mr Dodd, who was very excited and asked when I could start.

“I said, ‘Tomorrow!’

“When I got there, Mr Dodd took me to the pattern room. I did a test and did excellently well.”

‘I’ll take her if you don’t want her.’

Despite her obvious flair and the unwavering support of Mr Dodd, Grandma didn’t get the job.

“They sent me out,” she confesses. “They said they didn’t want any black people there. The factory employed more than 1,000 people, but none black.”

“Wow.”

Mr Dodd, the head of a separate department, knew what they’d be missing.

“Mr Dodd said, ‘I’ll take her if you don’t want her.’ So that’s how I started working in Mr Dodd’s office.’

He gave Grandma a little warning before starting.

“He said, ‘Bring your food in from home because I don’t want you to go to the dining room yet.’ So I was getting my food in from home and eating in the cutting room.

“Then one day, Mr Dodd called a lady over and said, ‘Take Lola to the dining room.’ She laughed and said, ‘You mean it?’

“When we got there, we sat down with our food… and the next thing I heard was this noise.”

The deafening clang of banging cutlery, plates and glassware rip-roared across the cafeteria.

“’Ah-ah, what’s that?’ I asked.

“The lady who took me there said that they were complaining… that they had brought a black person into this place.

“I asked, ‘Should we go?’

“She said no, that they would get used to it.”

‘I’ve never seen a crocodile or elephant in my life!’

The lunchtime protests continued for several days, becoming less and less rowdy each time. They were indeed ‘getting used to’ Grandma, their first and only black colleague.

“After 2 or 3 months, they started coming to talk to me.”

Disapproval slowly and surely turned into curiosity and intrigue. She was allowed to eat at their tables, take the bus home with them – and they wanted to know all about Nigeria. She didn’t really mind this, and actually found it quite amusing.

“They would say things like, ‘Anytime you’re going to Nigeria, bring me skin of elephant and skin of crocodile.” I’d tell them, ‘I’ve never seen a crocodile or elephant in my life!’”

“I want to know a bit more about Mr Dodd; it seems like he was your main supporter?”

“If not for Mr Dodd, I wouldn’t have enjoyed the place.”

Grandma gives me a brief history on her former boss, which explains a lot.

“One day, I was talking with Mr Dodd. He said he had two children; a boy and a girl.”

She tells me how Mr Dodd’s daughter had brought a Jewish man home, of whom they did not approve. Their son, on the other hand, married an English woman.

“About 2 weeks after the wedding, they left England for South Africa. Their daughter’s husband – the one they did not approve of – came to them and said, ‘That house that is 2 or 3 houses away from you… we are buying it so we can be closer to you.’

“What really changed [Mr Dodd] was that this Jewish man became their son. God sent him to replace the one they lost to South Africa. The one in South Africa would send greeting cards at Christmas. But their son-in-law was the one looking after them, doing their shopping.

“From there, he made up his mind that he would never discriminate again.”

Chapter 4: Fencegate

Our conversation takes an even more harrowing tone when I ask about any experiences of racism outside of the workplace. I’m shocked to hear of an incident involving one of her young children.

“There was one day. Yinka was on the street playing – it was summer. I was a the Butcher’s shop when about two or three women came to me shouting:

‘Mrs Ogunlesi! Mrs Ogunlesi! Come, come! Lola! Lola!’

‘What is it?’

‘Just come, just come!’

“By the time I got there, Yinka was lying on the floor [unconscious]. We took him to the hospital. The questions the doctors and nurses were asking, I couldn’t answer because I wasn’t there. But the people who were there, they were answering the questions.

“A white girl had pushed him. Maybe about three or four years older than Yinka. Yinka had climbed the fence in her garden. The girl went behind him and pushed him down. He hit his head and passed out.”

“Wow.”

“So, he spent a few days in the hospital, about five days.”

‘We were living with enlightened people who were happy to be living with foreigners.’

Grandma goes on to explain that the community were very supportive of them and reprimanded the girl harshly on the family’s behalf.

Despite these experiences, she still maintains that she had a pleasant time on the whole and felt accepted by most of the people she met.

“They all loved us,” she continues. “Real love.”

“Apart from those instances, we were living with enlightened people who were happy to be living with foreigners. And at that time, remember, there were just a few of us. On that street, out of maybe fourteen or sixteen houses, only two families were black.”

A part of me wonders whether my grandparents’ relatively seamless integration into British society was possible due to their being two educated, well-spoken young professionals living in Manchester’s most affluent suburb.

But ultimately, I don’t doubt that they were also just likeable people. Either way, it’s nice to hear how generally well-treated they were.

As idyllic as this may sound, Grandma explains that racism was certainly a problem in other parts of the country, and that as the black population continued to steadily rise, so did racial tensions.

Chapter 5: Homecoming

“The discrimination that black people faced after us? Ahhh. It got very bad. That was the time we were preparing to come home.”

In 1972, after 10 years in the UK, my grandmother and her family returned to Nigeria. Their English friends were sad to see them go. They would come to their house to cry and beg them not to leave. But their desire had always been to bring their studies and skills back to their homeland, and that’s exactly what they did.

“That was when we started reading about it in the papers.”

Racism was particularly rife in Britain in the ‘70s and ‘80s. And purely for contextual rather than political purposes, I’ll remind you that the late ‘60s and early ‘70s saw the infamous Enoch Powell speech and Conservatives coming into power. As well as institutional racism, such as was evident in the police and criminal justice system, overt racism was far from uncommon.

Black people were subject to violent racial attacks, particularly from far-right groups like the National Front. Black footballers were having bananas thrown at them. Black communities were (and still are) over-represented in the most deprived and poverty-stricken parts of the country.

Although things seem to have improved on a surface level, systemic racism, racial inequalities and racial prejudice are still deeply embedded in the fabric of the British nation. I think we can blame this at least in part on the absolute lack of Black British history in the curriculum.

Failure to learn lessons from our past inevitably leads to ignorance and stagnancy, as history repeats itself.

My grandmother is a remarkable lady and I thoroughly enjoyed this time of soaking in her stories.

Within the context of the historical timeline of Britain, and the socioeconomic status that they enjoyed, it’s not difficult to understand why they were – on balance – able to have such a good life.

Like my grandma, I’ve had many, many lovely people in my life who are white.

As I reflect on my own experiences growing up in predominantly white communities, I wonder whether some of the acceptance that I have been afforded has been conditional on commonality. I’ve certainly experienced first-hand a demonstration of this kind of acceptance through the explicit praising of my ‘coconut’ qualities.

But is that enough? (Or healthy ?!).

As a society, we have a long way to go towards the fair treatment of black people regardless of class, background or resemblance to the majority.

When it comes to the idea of what constitutes being British, we need to accept that there is more than one way to be British. A black British person with fewer ‘quintessentially British’ quirks than me is still a black British person.

Grandma loved her time Britain, but she was and is a Nigerian through and through. I love being black. I love my Nigerian heritage and learning about the history and the stories that brought about my existence. I also love being British. I love all the idiosyncrasies that make me who I am: Christine.

Human beings don’t belong in societal boxes. I can’t be bothered to adjust my personality to suit my audience, nor do I have to.

Claiming and embracing my birth-given British-ness does mean that I’m trying to be ‘white’ . Nor does it make me any less ‘black’. It means that I’m claiming and embracing my birth-given British-ness.

To anyone, anywhere – whatever your race, colour or background – who consciously or subconsciously believes that black people cannot ascribe to British culture, opportunities or nationality, please hear me when I say:

I am black and I am British.

Xtine

A very special thank you to my grandmother, Mrs Adedoyin Titilola Ogunlesi. She would like to leave you with this message: “Whoever you are, don’t discriminate. We are all human beings.”

In memory of my beloved grandfather, Engineer Owolabi Ogunlesi. 13 years without you, but your legacy lives on in your descendants forever.

In memory of my amazing grandmother, Madam Olufunmilayo Olumuyiwa, the most loving person I ever met and the most impossible to forget.

Love it. I like the fact that she spoke about the positive and otherwise. I remember educatio. in the sixties. A primary school where three of us were black in the entire school. We were pampered and treated so favourably (only because we were different). I can only remember kindness from the teachers. Yet there was an incident of young silly puppy love. I had this friend called Paul and I was so in love(hmm…at 7 years old). In our silliness we talked about marriage (we seemed to be smitten with eachother) So we sent eachother off to our respective families to say ee had found some (can stop laughing). We the long and short of it was I wouldn’t dare discuss such a stupid issue with my parents… they would have killed me!!!

He came back with some bad news… unfortunately you are black. Such a union will not be allowed in his family.

I was disappointed but there was this acceptance. I guess somewhere deep I began to get it. Just shows in life, there are the good, the bad and the ugly. I will determine what I want to be by His grace, a lover of my neighbout no matter culture, gender, race, age, ability, sexual orientation and most of all colour!

Wow!!! What a sweet story, thank you so much for sharing, auntie. It’s great to hear your input. I’m glad you loved this too. It’s so enriching to hear about that time xx

Well done Dr CS, excellently put together. Keep it up dearie.

Thank you so much!! Xx

Keep it up my doc, you are a born writer. I thank God for your life. My dear obeeee.🤣.I suggest you make it like novel (book). What do you think. Loving you always. Auntie Sunmbo.

Aww, my auntie!! Thank you so much, I’m glad you liked it Ma. Love you too!! Obeee xx

As before, so well written. I loveGrandma’s input here.

My take home message is to be who you are irrespective of what others want to pigeonhole you as. Ultimately we are all making our own journeys through this life and the lovers will remain as will the haters. Consciously or unconsciously.

By our actions and attitudes many will learn that we are one human race.

Keep up the good work Christine

Thank you so much auntie, that was one of the main take home messages I was hoping for so I’m very happy to hear that!! Xx

you are obviously a nice person & thoughtful gran daughter , Thank you for your good insight into back in the day questions that are still very relevant & have considerable importance to this very day. It was interesting to learn more of your immediate family history & the balance that prevails within some uncertain times & how sense of humour & courage of conviction will always win the day, thank you for sharing this of you & my Auntie

(Lola x ) also Toyin ,Tola, & Yinka just to add.. no body can be you but you ..

John Akin Tola Fagbore

Hi, Uncle John! I’m so touched, thank you for reading and for your lovely words. I hope it was special to you as part of the family and as someone who also experienced life in those times first hand. I’m glad to add in any small way to these conversations xx

Love this Christine! You are amazing and this is so thought provoking…. I also think your grandma is kick-@ss! What a groundbreaker working and raising kids in that era…..

Haha! She is indeed! Thank you so much Katy xx

We are more than a conqueror through Christ Jesus. Grandma had strong faith and believes and still believes in herself so much. She is so strong-willed and determined and her life reflected just that.

Now you have opened my world of memories to those days- down the memory lane.

The voyage back home to Nigeria, on ‘The Ariel’- is and will always be an unforgettable experience. Yes! I will never forget. That two-week cruise on the Atlantic Ocean, through the shores of many countries, back to West Africa, is a vivid memoire. The imagery of the crystal blue waves, lapping against the ship, the golden sandy beaches plus the sea sickness. The excitement of finally meeting our family and being treated like little princesses and prince. What a great experience never to forget!

Mission Possible!!!

Yes. They did. They fulfilled their plan and purpose and brought back a wealth of skills and expertise, making great impact on their community and wider, through God’s special grace. Why? The following fruits were applied: patience, humility, perseverance, self-control, love and lots of hard work by God’s special grace. To God be all the Glory!!!

The Great Message-The Golden Rule

We must always embrace the simplicity of truth – we are all unique and special in Gods sight irrespective of skin colour or cultural differences. We are all loved by one God who teaches to love one another. We must always do unto others what we want others to do unto us [golden rule]. To fulfil our dreams we must continue to persevere and never give up, no matter what challenges we encounter in life, keep travelling, we don’t need to get to the end of the tunnel to find light-light meets you on the way. We must seek help if we feel we are totally lost! We must totally trust in God and he will shine is light so you can illuminate and touch other lives positively. The world can call us one name, but God gives us a great name. It’s called ‘Victory’

Wow, what beautiful words mummy. Love you lots xx

I am short for words Christine, this is beautiful and whilst I know you, all of us are Black, Beautiful and unapologetically proud about it, I never knew you were this passionate about it.

The write up is lovely and educative. We have so many things to be thankful for. Our beauty is unstoppable, unshakable because it is well rooted in our rich culture and enduring faith.

Well done, really proud of you.

Thank you so much for reading auntie. You’re right, there’s so much beauty in our culture and faith makes all the different. Knowing who we are makes it difficult to buy into a narrative of stereotypes – we are so much more xx

Thank you for your thought provoking perspective. Something I could relate to. Beautifully written. It was also great to have your grandma’s input.

Thank you so much! Xx