The air is thick with the heat of this 31°C evening in the open-air communal area of Hostel Mamallena. Humid or not, I’m all dolled up and ready to explore colourful Cartagena. My time is coming… but for now, I’m content to patiently exist in this moment. As I wait for my friend, I stop to take in the aesthetics of these quaint living quarters.

The majestic-looking tree to my left, towering over its evergreen younger siblings, its branches disappearing into the open sky above me. I look down at the polished wooden table which is now accommodating a furry little intruder. I mean, I’m no cat person, but this little guy is adorable with those Puss-in-Boots eyes. He saunters over and hops into my lap instinctively. This isn’t so bad.

The city outside awaits, bustling with excitement, beauty, culture, history, music and adventure. But this undemanding moment in time is utterly serene and oddly perfect.

“Ça va?”

*Insert disc scratch sound effect with a side of Krusty-Krab-meme-level confusion.*

For 0.3 seconds, I don’t know where I am. I’m pretty sure they don’t speak French around here.

Earth to Chris!

“Er, oui… ça va bien,” I reply, perplexed.

I confirm that my kitten and I aren’t alone anymore, as I turn around to find a 6 ft-something sturdily built Nikolaj Coster-Waldau lookalike smiling down at me. Mid-40s, at least. He proceeds to let out a monologue of beautiful French as I take a few seconds to reorient myself.

“Wait!” I laugh, knowing full well that I’ve exhausted my knowledge of the language. “¿Hablas inglés?”

“Yes,” he replies with a nervous chuckle.

Loooool? What is going on here? Why did this random guy assume I could speak French? No idea, but it’s hilarious.

I’m not naïve enough to expect that this conversation isn’t going to go a certain way, but I’m rolling with it. What’s my name, what am I doing in Colombia, what am I doing later etc. etc. etc.

“I grew up in Rhodesia,” he shares, unsolicited. “My parents moved there from Switzerland and I was so devastated when we had to leave, I had a beautiful childhood.”

“Oh cool, where’s that?”

He stares at me in disbelief. “Zimbabwe…” he answers in an ‘obviously’ tone.

Oh THAT’S where we’re going with this.

“Oh wow, I didn’t know that. That sounds nice.”

He gazes at me intently, as I try to put my eyes anywhere else. “You know… I’ve always loved African women.”

Ugh.

Who said I was African?

“Ha ha. Well, we are amazing.”

“Yes, you are,” he agrees with a grin. “And… you’re a very beautiful woman. I- I don’t mean to make you uncomfortable.”

So we’re on the same page, then. This is uncomfortable. Cool.

“Ha, thank you. That’s kind of you to say.”

His lips aren’t moving now, but his eyes are saying, “my room is right behind you.” I’d never really understood the phrase “piece of meat” before, but for some reason, that’s how I feel. Delectable. Like exotic fruit. Like his favourite flavour of ice-cream.

Fortunately, our conversation comes to a swift natural end, with Puss-in-Boots still purring away on his comfy thigh-bed. I wonder what he makes of the peculiar interaction.

‘More to me’

This was one creepy encounter. I’ve heard about dozens more, and some not quite so hands-off. The same skin that has inspired hatred and discrimination for centuries is the same skin that’s apparently some sort of fetish. How am I supposed to feel about this? Flattered?

You’d be forgiven for wondering what the issue is. ‘So, he likes African women. Why shouldn’t he? Isn’t that a compliment?! People are allowed to have preferences, aren’t they? Why is this any different?’

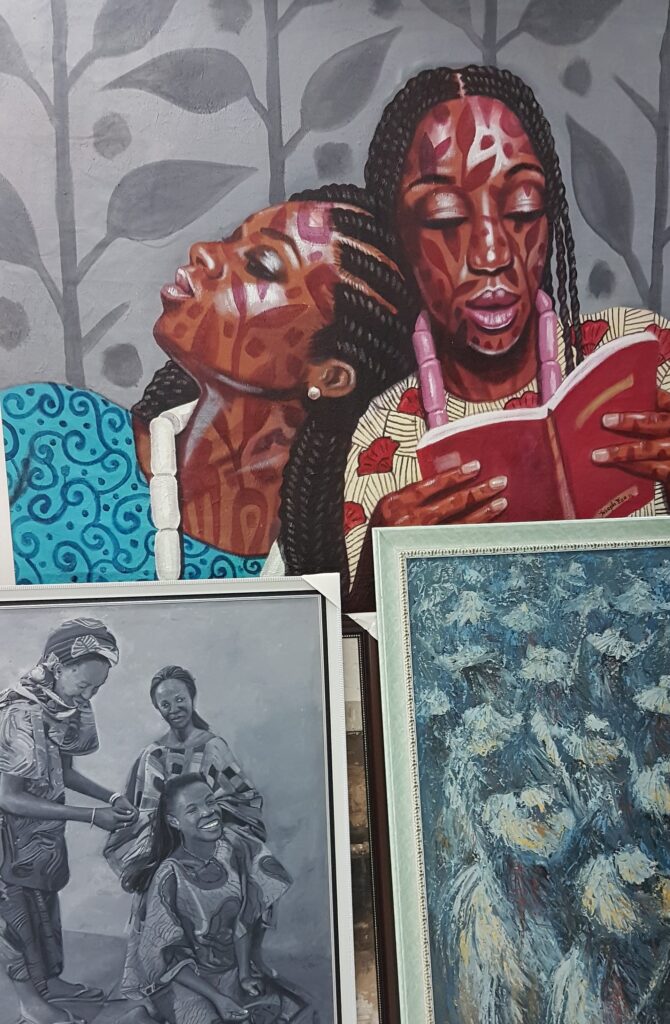

We all have preferences in life which lead us to pursue different things. I find nothing wrong with a white guy having a natural, innocent and genuine liking for black girls. But this didn’t feel natural, innocent, or genuine. This was fascination. My brown skin was intriguing. I was a piece of artwork being admired in a gallery. It sounds nice, but it isn’t.

I’d rather be a person.

He wasn’t interested in me; he was allured by my presumed foreignness, enamoured by colonial nostalgia.

Even if he quite simply and genuinely loved and appreciated African women, he could have approached me without making it explicit; without reducing me to my race. Instead, he decided to make a point of it. Why do that?

Even if only subconsciously, he was exerting his power as a middle-class white man in a society underwritten by racism and misogyny. The expected result: a grateful, poor black woman, who feels privileged to be wanted by an older white man, and flattered to have been noticed at all. It’s not said, but it’s heard.

Political undertones aside, being made to feel that your attractiveness lies in a singular physical attribute takes away from your multiple attractive qualities. Your other physical features. Your unique personality, your intellect, your passions, your sense of humour, your soul. There is more to me than my blackness.

I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt, though. It’s possible that he really didn’t mean to make me uncomfortable. Perhaps he was perfectly well-meaning, and just made some comments which unfortunately didn’t go down too well.

And I know firsthand that being African (which he specified) encompasses more than a skin colour. It’s an array of wholesome and enriching cultures and hey, I guess he did grow up there. Maybe the qualities he finds attractive aren’t merely skin deep. Maybe they aren’t solely based on stereotypes about the black woman’s body. (Maybe).

‘Pretty for a black girl’

Unwanted male attention isn’t the only thing women of my skin-tone have had to deal with over the years. Black women face the consequences of bias and prejudice daily, from experiences in the workplace to the detrimental effects of health inequalities.

I almost had to grow up without a mother. After enduring the pangs of labour and bringing me into this world, her concerns that something was wrong were repeatedly ignored. The woman who gave me life ended up fighting for hers as she was rushed into theatre with a massive postpartum haemorrhage, secondary to retained placenta. (God knew I needed her).

Unfortunately, this isn’t an isolated anecdote. Black women in the UK are five times more likely to die from complications related to pregnancy and childbirth. Why? There isn’t one answer. Susceptibility to certain medical conditions as well as socioeconomic factors (usually the result of racial inequalities) probably contribute.

But – at least in part – the stereotype of the ‘angry black woman’ has reduced us to chronic complainers, whilst the stereotype of the ‘strong black woman’ speculates that we possess superpowers. And I don’t mean telepathy, X-ray vision or invisibility. I’m talking about numbness-to-pain and superhuman-resilience. There’s an assumption that we’ll “be alright.”

Then there’s the other end of the spectrum of perceived beauty. Is being told that you’re “pretty for a black girl” – or even better – “for a dark-skinned girl” supposed to be a compliment? Really? The subtext is that, by default, dark-skinned women aren’t attractive. I’ve known black and non-black men alike to say it straight up: “I’m just not attracted to black girls.” Okay, that’s absolutely fine – each to their own. But, have you taken a moment to ask yourself why?

These sorts of ways of thinking are often deeply rooted in systemic racism. You may have heard of the phrase ‘proximity to whiteness’ which presents the idea that as a society, we have been conditioned to be more attracted to lighter skin and whiter features. Just look at the skin-bleaching epidemic. The word ‘fair’ is literally synonymous with beauty. Where does this come from?

In the 16th century, European colonisers sought a commodity to generate wealth in order to build and sustain empires that would dominate the world’s economy. One that would bring in maximum profit at minimum cost. They turned to the not-so-neighbouring continent of Africa and – as I’m sure you’re aware – the commodity they were looking for was its people.

Black humans were exchanged for goods and weapons, and in some cases, captured. For centuries, they would live and work as slaves, serving under masters in foreign lands, with no value other than monetary. The ‘free manpower’ behind the cultivation of lucrative and incredibly labour intensive crops such us sugar and cotton. This wasn’t the first enslavement of black Africans in history; the precedent had already been set on a smaller scale by some pre-colonial civilisations.

I always ask myself: why black people?

Well, for one, colonial European citizens had rights which meant they couldn’t be forced to work without payment. And these guys were looking to hit the highest. profit. margins. possible. So, that wasn’t really going to work. Hence, slavery was their logical solution.

The indigenous Americans were far too familiar with their own land to be easily controlled (…and were dying at an alarming rate from European illnesses and genocide), which probably led them to look abroad. West Africa was likely chosen for its proximity to sea ports and the establishment of a clear path for transportation across the Atlantic. And Africans happen to be, for the most part, black.

But… I don’t know… something tells me that their blackness wasn’t as inconsequential as this logistical and ‘just-so-happens’ notion implies. Surely, there must have been some preconceived ideas about black people to make them think they could get away with this.

Maybe it was the connotations of evil, negativity and fear attached to darkness.

Maybe their prominent facial features, and the striking contrast with their own white skin, were deemed too disparate to be considered human. And if they weren’t human, then they weren’t deserving of human rights. From a practical sense, these obvious physical differences would be ideal for distinguishing slaves from citizens.

Maybe their peculiar customs and unfamiliar behaviours made them appear to be an uncivilised, unintelligent people who needed Europeans to enlighten and subdue them. (…the same sense of entitlement that I imagine led them to claim land at will).

Perhaps it was a combination of these things. Or something else entirely. I guess I’ll never fully know.

But where does this idea of ‘proximity to whiteness’ come in?

It wasn’t uncommon for female slaves to be raped by their white owners. They were not viewed as people, but as sexual objects existing purely for service and pleasure. Many of these women – if they fell pregnant, and if those pregnancies actually made it to term – would bear their masters’ children.

The fairer complexion of this generation meant that they were often promoted to the position of ‘house slave’ and spared from long days out on the plantations. They were also more likely to receive an education, and were generally favoured over their darker-skinned peers. This was particularly true of the women.

‘Sassy best friend’

The ripples of slavery on the perceptions and treatment of black people have been experienced long after its condemnation. It may have been abolished, but everyday we are all being spoon-fed the idea that ‘white is better.’

Our education systems remind us of our oppression, whilst failing to highlight the history and significance of black people outside the context of slavery. We don’t hear about the black explorers who set sail before Columbus, or the ancient African civilisations that were thriving outside of Egypt. They pacify us with one measly month each year, when we’re permitted to talk about the same isolated stock figures from Mary Seacole and Rosa Parks to Nelson Mandela and Dr King.

Our institutions uphold and sustain systemic racism. Widely accepted terms like “people of colour” perpetuate the idea that white is the standard. Black women are still objectified as a result of hypersexualising stereotypes rooted in our traumatic history, whilst on the other hand, are rejected for anything meaningful for being ‘too dark.’

Dark-skinned black women are still viewed as less desirable than our lighter-skinned counterparts.

The quest for proximity to whiteness has produced an insidious light-to-dark hierarchy within the black community – a concept known as ‘colorism.’ It exists within the black race, but also permeates into mainstream perceptions of the black race.

We all know that the media we consume affects the way we perceive ourselves and each other. The sustained lack of darker-skinned black women portraying protagonists and love interests in mainstream TV series and big-budget Hollywood films has left a lot of black girls feeling invisible. Halle Berry is talented and stunning, but she does not represent black women in our entirety. We rarely see a dark-skinned black female character amount to more than the ‘sassy best friend.’ And the industry’s obsession with the commercial potential of ‘slave films’ perpetuates the image of dark-skinned black females as ‘slave women.’ So, we turn to our guilty-pleasure Tyler Perry movies and humble gems like The Best Man (1999).

Even when it comes to predominantly black films and TV shows, light-skinned black actresses are usually cast to play the desirable women and love interests. In some cases, they have even replaced previously cast dark-skinned black actresses in established roles. Jennifer Freeman replaced Jazz Raycole as Claire on My Wife and Kids. Daphne Maxwell Reid replaced Janet Hubert as ‘Aunt Viv’ on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. We may not know all the details behind these decisions, but one thing is quite clear – the impact that these changes were bound to have on the dark-skinned girls who saw themselves in those characters. Like me.

‘Melanin-rich’

One of my favourite childhood films is Rodger’s & Hammerstein’s Cinderella (1997). Imagine; a beautiful dark-skinned black woman (with braids!) playing not only the title-character, but a well-known and well-loved princess who is historically white. She’s portrayed as gentle, kind, desirable and worthy of love. The representation in the film as a whole is exemplary. Another loved character that comes to mind is the witty, articulate, and ridiculously gorgeous Angela from Boy Meets World (1993 – 2000).

It’s a struggle to conjure up many more examples. Why weren’t we exposed to more of these types of characters? As a young dark-skinned girl and film-lover, I was painfully aware of the absence of people who looked like me on-screen. When they were featured, they were usually portrayed in the most unflattering ways. I found myself believing that white and lighter-skinned black girls were prettier, smarter, kinder, more interesting… better. I found myself wishing I looked like them. It played a huge part in the belief that I was ugly, making it inherently difficult to love myself.

What was it that the media didn’t like about me? What made my appearance so unpalatable? Maybe it was the connotations of evil, negativity and fear attached to darkness…

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve made a conscious decision to appreciate, take stock of and celebrate the dark-skinned black women who are incredibly beautiful to me. Naomi Campbell. Whitney Houston. Kelly Rowland. Sarah Jakes Roberts. Kerry Washington. Lupita Nyong’o. Gabrielle Union. Tika Sumpter. Nia Long. China McClain. To name a few; and not to mention my gorgeous girlfriends, the lovely ladies in my family and all my melanated WCWs on the Gram.

As much as this has undoubtedly helped with my self-image, I have ultimately had to recognise and internalise my own beauty. NO ONE can tell me that my melanin-rich glowey chocolatey DARK skin is not S.T.U.N.N.I.N.G. So, I guess I can see why the Swiss guy was mesmerised by my complexion. But, let’s learn how to appreciate the true beauty of the dark-skinned woman – inside and out, with all her complexity – and do so with respect.

Slowly but surely, things are changing. Even so, we have a long way to go in terms of reversing deeply ingrained societal views towards black women and black people in general.

We need better representation in all industries, not just entertainment. But using it as an example; it starts with seeing more successful black-owned production companies, more contemporary mainstream characters like Marvel’s Shuri (representing black women in STEM), more high-calibre films telling black stories like Hidden Figures (2016), and simply (and in a way, most importantly) normal, everyday stories which just happen to be about normal, everyday black people.

As much as there should be a call for better representation, black women shouldn’t need to rely on representation to realise our beauty and worth. We need to know and live this, intrinsically, at all times.

Dear black women,

It’s time to take back the pen. Let’s rise up into positions of influence. Let’s support each others’ ventures. Let’s be authors of our own history as we actively change the narrative that’s been written about us. I feel privileged to be able to play a small part within the field of healthcare. I pray that young black girls with an interest in medicine would be encouraged to dare to pursue their ambitions. I hope that every service-user I encounter would feel listened to and taken seriously – especially the black girls and women who’s concerns have been disregarded for too long. And ladies, it’s okay not to be strong. We are allowed to be vulnerable, we are allowed to need help, and we deserve to be heard when we speak up. We are beautiful, smart, desirable, attractive and all of the like – and I’m sorry that we haven’t always been made to feel that way.

Dear black men,

You face your own unique trials. We as black women need to stand up for you – in the same way, please stand up for us. Please don’t perpetuate the stereotypes that hurt us. Instead, protect and support us in unity. Appreciate us, value us, love us. We don’t need you to treat us like queens; we just want you to treat us with respect. We are your sisters, mothers, daughters, wives, partners, aunties, nieces, friends. We’re in this together.

Dear non-black brothers and sisters,

I’d urge you to search yourselves. Make a conscious decision to identify, acknowledge and dismantle the biases and worldviews you have subconsciously acquired since birth. It’s uncomfortable, but so are racism, colorism and sexism. If you have ‘a thing for black girls’ – or if you ‘don’t see them in that way at all’ – challenge yourself to ask… ‘why?’ Take a moment to pause before you give us a black-handed compliment (yes, black-handed). These issues are so complex. Do your research. Educate yourself. Then, do something about what you’ve learnt. Lobby for changes to our curricula. Sign petitions. Call things out. Support black-owned businesses. Care. Do what you can.

‘Not of this world’

We are all created in the image of God, and this goes beyond our physical appearance. We exist in a world where race matters – for obvious reasons. Race cannot and should not be ignored, and “I don’t see colour” is neither noble nor true.

As a Christian, I have to remember that I am in this world but not of this world. Before I am anything – black, African, a woman – I am a soul, won by Jesus Christ. For this reason, these issues don’t define my existence. I’m still passionate about them, and I’ll continue to talk about them as long as they continue to affect my people. But I find peace in knowing that God sees things so differently to us. In the last days, it won’t matter what we look like or where we’re from.

“…For the Lord does not see as man sees; for man looks at the outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart.” 1 Samuel 16:7

“For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Galatians 3:27-28

For a dark-skinned girl:

You are not beautiful simply because you are black.

You are not beautiful despite the fact that you are black.

You are beautiful… and you are black.

Xtine

Another well written piece Christine. So relatable on so many levels.

It’s often easy for people like us to forgive and accept the micro aggressions we experience whether deliberate or not. So I like the challenge you have put to the non-black readership to enter their own territory of discomfort and question their behaviours/attitudes also.

Equality will only come by having difficult and uncomfortable conversations with oneself or others.

You are a beautiful black woman indeed. Inside and out ❤️

I can’t wait for the next read.

Auntie Px

Thank you so so much auntie, it’s so lovely and encouraging to hear that. I’m humbled and glad that you’re enjoying and engaging with the reads ❤️ xx